One of California’s most powerful political forces may have peaked

Feb 25th 2010 | LOS ANGELES | From The Economist print edition

How much longer will they hold the keys?

How much longer will they hold the keys?DON NOVEY used to be the most important man in Californian politics that no one had ever heard of. As president of California’s prison-guards’ association from 1982 to 2002, Mr Novey turned that union into the most powerful in the state. On his watch, California built 21 new prisons. Mr Novey’s organisation also sponsored or supported tough laws that helped to fill those prisons to almost twice their capacity at times. It helped elect two Republican governors and one Democratic one, besides countless state legislators. “We sent candidates 13 questions,” he happily recalls, ranging from their stance on the death penalty to labour issues.

He is especially proud that he won his members by far the most generous wages and benefits that prison officers get anywhere in the country. Under the last deal he negotiated, which expired in 2006, the average member of the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA) earned around $70,000 a year and more than $100,000 with overtime. (Since then, wages have gone up again.) Mr Novey negotiated pensions of up to 90% of salary starting at as early as 50—more than teachers, nurses or firefighters get, and matched only by the state’s highway patrol.

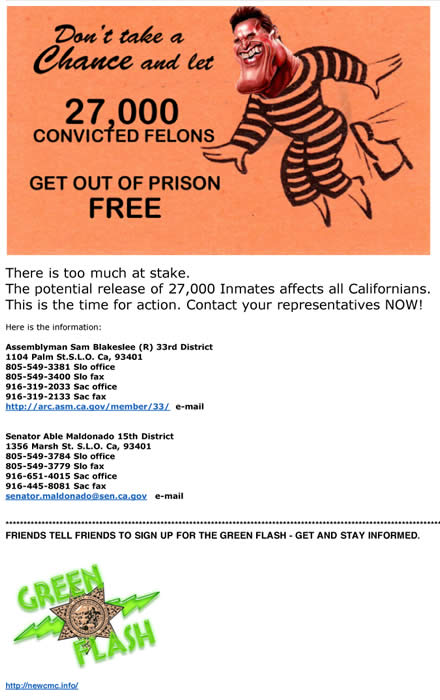

This is the legacy that many people now blame for a good part of California’s fiscal crisis. Visiting the state earlier this month, Anthony Kennedy, a justice on the US Supreme Court, said it was “sick” that the CCPOA had sponsored the “three-strikes” law of 1994, a notorious sentencing measure that contributes to prison overcrowding. The state’s prison agency is permanently at war with the union and accuses it of obstructing reform. California’s governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, had to climb down from open confrontation with the CCPOA in 2005, but is now proposing to privatise much of the state’s prison system precisely to evade its grip.

The CCPOA (which did not reply to The Economist’s repeated requests for interviews) returns the hostility. In its view, prison guards “walk the toughest beat in the state”, as its motto has it. In the Peacekeeper, the union’s newspaper, the editor writes that guards “protect the good people of the world from the bad people”, while another entry reminds guards that “if you have been gassed and exposed to blood-borne pathogens…know that every minute counts.” This is no ordinary job, the union insists, and its members deserve a good deal.

Yet the CCPOA’s influence may be waning, says Adrian Moore at the Reason Foundation, a think-tank in Los Angeles. In Mr Novey’s days, the union might have won an exemption from the furloughs of state workers now necessary because of the budget crisis; these days, it appears unable to. Barry Krisberg at Berkeley’s law school says that the guards “have priced themselves out of the market”. They can’t push for even tougher laws, he says, at a time when prisons are so overcrowded that a federal court is threatening mandatory inmate releases. And they can’t demand even more generous benefits during a fiscal catastrophe. The iron triangle—union, prison builders and Republican lawmakers—is coming apart, he thinks. Mr Novey agrees; and many Californians are hoping they are right.

No comments:

Post a Comment